In many companies, outdated software remains in place far longer than originally intended. The reason is usually practical rather than strategic: the software continues to function. Transactions are processed, reports are generated, and daily operations are not visibly disrupted. From a short-term perspective, replacing a working system can seem unnecessary.

Modernization, however, is rarely initiated because a system suddenly fails. It is more often driven by accumulated constraints: slower delivery cycles, higher maintenance effort, increasing infrastructure costs, or rising security concerns. These signals develop gradually and therefore tend to be deprioritized.

Outdated software does not typically stop the business. Instead, it changes how the business operates — subtly, incrementally, and often without formal recognition.

How legacy systems begin to shape the organization

The impact of legacy infrastructure becomes clearer when new initiatives are introduced. Consider a company launching a new digital service or integrating with a cloud-based analytics platform. The business objective is well defined, and the implementation plan appears realistic.

During execution, however, teams encounter architectural limitations. Existing systems may not support modern API standards. Business logic may be embedded in stored procedures written years earlier. Documentation may not reflect the current state of the environment. Changes require extensive regression testing because dependencies are tightly coupled and not fully transparent.

No single obstacle is critical. Yet collectively, they extend timelines and increase costs — a common pattern in environments where software outdated platforms constrain delivery.

Over time, these experiences influence organizational behavior. Project planning becomes more conservative. Technical risk assessments expand. Certain improvements are postponed because modifying core systems introduces uncertainty. The technology environment begins to define what is feasible rather than simply enabling business objectives.

Security exposure in unsupported environments

The end of vendor patch cycles

When software reaches end-of-life, vendors discontinue regular security updates. The system may continue to function normally, but newly discovered vulnerabilities are no longer addressed through official patches, increasing overall outdated software risk.

Organizations can implement compensating controls such as network segmentation, enhanced monitoring, or restricted access. These measures mitigate risk but increase architectural complexity and operational overhead.

The longer unsupported systems remain in operation, the more they diverge from current security standards. Encryption protocols, authentication mechanisms, and access controls that were once adequate may no longer align with contemporary best practices, creating outdated software vulnerability exposure.

Regulatory and operational implications

In regulated industries, unsupported software often attracts scrutiny during audits. Organizations may be required to demonstrate how security risks are mitigated despite the absence of vendor support. Documentation requirements increase, and justifying continued use becomes more complex — especially when auditors identify outdated software security risks.

If an incident occurs, legacy infrastructure can complicate response efforts. Older systems may lack advanced logging capabilities or integration with centralized security monitoring tools, making forensic analysis more difficult.

Security resilience depends on ongoing updates and architectural adaptability. Legacy platforms limit both.

Performance and scalability constraints

Infrastructure built for different conditions

Many legacy systems were implemented in environments with smaller datasets, fewer integrations, and lower concurrency demands. As organizations grow and digital interactions increase, these original design assumptions may no longer hold — a frequent scenario seen in outdated system software.

Performance issues typically develop gradually. Query response times increase, batch processing windows expand, and infrastructure teams allocate additional resources to maintain acceptable service levels. Vertical scaling through hardware upgrades may postpone bottlenecks but does not resolve architectural rigidity.

These adjustments increase cost without necessarily improving flexibility.

Operational consequences

Performance degradation affects more than system metrics. Slower reporting can delay planning cycles. Inconsistent application responsiveness may influence customer experience. Increased resource consumption raises operational expenditure.

When performance limitations begin to influence planning decisions or restrict new initiatives, the issue shifts from being technical to operational — one of the core outdated software issues.

Technical debt and organizational impact

Technical debt accumulates through incremental design compromises and deferred improvements. Over time, systems become tightly coupled, and core modules support multiple interdependent processes.

Development teams in such environments often conduct extensive impact analysis before implementing even modest changes. Testing cycles lengthen. Maintenance effort increases. Innovation capacity declines because resources are allocated primarily to stabilization rather than enhancement.

Workforce considerations also emerge. Expertise in outdated technologies becomes less common in the labor market. Knowledge may be concentrated within a small number of long-tenured employees. This is often cited among real-world outdated software examples across enterprises.

Technical debt therefore affects agility, cost structure, and long-term sustainability.

Compliance and regulatory alignment

Regulatory requirements evolve continuously. Encryption standards are updated, logging requirements expand, and data governance policies become more detailed. Organizations must demonstrate that systems handling sensitive information meet current expectations.

Legacy systems can often be configured to comply with updated regulations, but doing so frequently requires additional layers of configuration, documentation, and compensating controls. Compliance becomes an ongoing operational effort rather than an inherent feature of the platform, increasing the risks of outdated software.

During audits, organizations operating outdated systems may need to provide detailed explanations of how risks are mitigated. This increases administrative overhead and potential exposure.

Organizational and strategic consequences

Slower decision cycles and reduced data visibility

Legacy infrastructure affects not only technical teams but also management processes. As organizations expand, leadership relies on real-time reporting and consolidated dashboards to support decision-making. When data models are rigid or reporting logic is embedded deeply in legacy code, generating new insights becomes a technical project rather than a configuration task.

Adjusting reports to reflect new KPIs may require changes in stored procedures, data transformations, and validation processes. This slows decision cycles and may lead departments to create parallel reporting mechanisms.

Over time, this fragmentation can result in typical outdated software risks:

- Duplicated reporting efforts

- Inconsistent metrics across business units

- Increased reconciliation work

- Reduced confidence in shared data

These outcomes stem from architectural constraints rather than isolated process failures.

Vendor dependency and ecosystem limitations

Legacy platforms often rely on proprietary technologies. As vendor support diminishes, extended support contracts may be required at premium rates. Negotiating terms becomes more complex, and cost predictability declines.

Integration challenges also emerge. Modern business tools typically rely on standardized APIs and cloud-native integration models. Legacy systems may require custom connectors or middleware, increasing maintenance overhead.

Vendor dependency can complicate partnerships, acquisitions, and system consolidation efforts, particularly when outdated software replacement becomes unavoidable.

Impact on mergers and restructuring

During mergers or acquisitions, IT integration is frequently one of the most complex tasks. Organizations operating outdated systems may face extended timelines for harmonizing databases, applications, and reporting structures.

Differences in unsupported technologies, custom-built modules, and version mismatches can delay operational alignment and cost synergies. In contrast, modern, standardized infrastructure typically facilitates smoother consolidation.

Migration strategy and risk management considerations

Modernization requires structured planning rather than reactive replacement. Before initiating migration, organizations should assess:

- Database complexity and embedded business logic

- Integration dependencies

- Performance baselines

- Regulatory requirements

- Internal expertise and resource capacity

This assessment allows prioritization of components with the highest operational or security risk.

A phased approach is often preferable to full replacement. Critical systems may be migrated first, while less sensitive components remain temporarily in place. Hybrid architectures can support gradual transition, reducing disruption and allowing validation at each stage.

Risk mitigation during migration includes clear rollback procedures, parallel testing environments, and data reconciliation processes. Automation tools play a significant role in reducing manual errors and improving consistency during conversion.

Defining measurable outcomes is critical to determine how to fix outdated software in a sustainable way. Organizations should evaluate modernization based on improvements in performance, maintenance effort, cost predictability, and audit readiness rather than completion timelines alone.

How modern software reduces these risks

Modern platforms are designed with continuous updates and scalability in mind. Regular security patches are integrated into standard maintenance cycles, addressing common outdated software risks before they escalate. Encryption and authentication mechanisms align with current standards by default.

Cloud-native databases support horizontal scaling, distributed workloads, and elastic resource allocation. Instead of relying solely on hardware expansion, organizations can scale based on demand.

Modern systems typically include:

- Integrated monitoring and observability

- Standardized API integration

- Automated backup and recovery

- Improved concurrency and indexing strategies

- Compatibility with DevOps and CI/CD practices

These capabilities reduce manual intervention and increase operational predictability. Development teams can deploy changes more frequently with lower risk. Security teams can rely on structured update cycles. Infrastructure teams can scale resources without significant architectural modification.

Modern platforms do not eliminate complexity, but they support structured management of change rather than reactive adaptation.

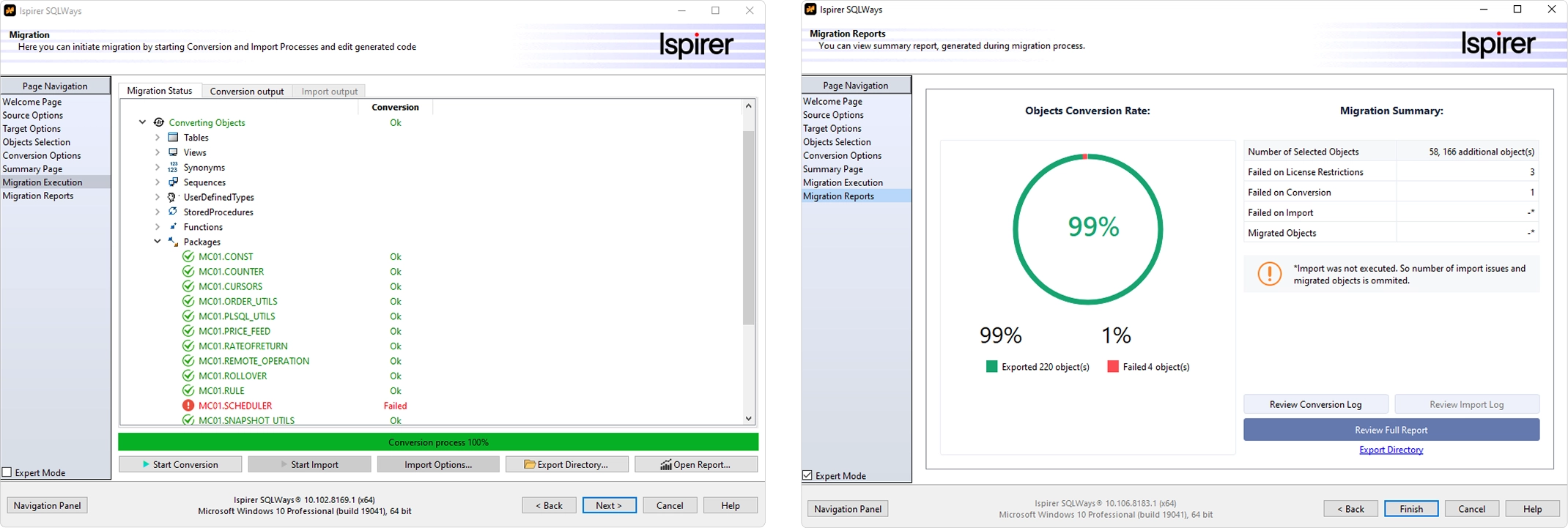

Database modernization with SQLWays

Database migration is often perceived as high-risk due to the complexity of converting schemas, data types, stored procedures, and triggers. Manual conversion in large heterogeneous environments increases the likelihood of inconsistencies and delays.

SQLWays, part of the Ispirer Toolkit, addresses this challenge through automated heterogeneous database migration. The tool analyzes source structures, object dependencies, and procedural logic before converting them to the target platform. Schema and data migration can run in parallel, reducing inconsistency between environments.

Customization capabilities allow conversion rules to reflect project-specific patterns, which helps preserve business logic integrity. InsightWays provides a pre-migration assessment to evaluate scope and complexity before execution begins.

This structured approach reduces uncertainty and improves predictability in modernization initiatives.

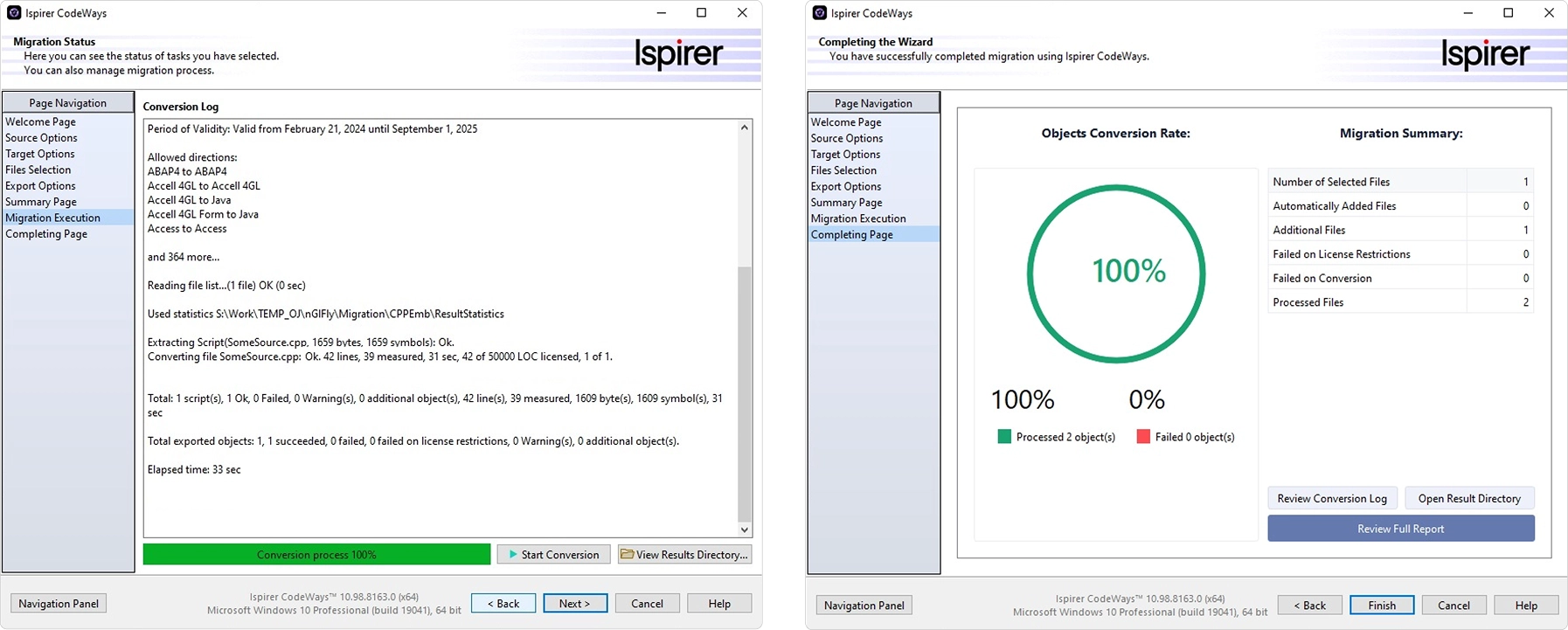

Application modernization with CodeWays

Legacy constraints often extend beyond the database layer. Applications built in outdated programming languages may limit scalability and integration with modern ecosystems.

If you’re wondering how to update outdated software, consider using CodeWays. It automates cross-platform application conversion, supporting transitions from legacy technologies to contemporary programming languages and frameworks. Instead of rewriting entire applications manually, organizations can convert a substantial portion of code automatically while preserving core functionality.

Where automation is insufficient, a hybrid approach allows targeted manual refinement of specific components. This balance between automation and customization reduces migration timelines while maintaining application stability.

Case examples

From legacy Sybase and Oracle to PostgreSQL on AWS

A U.S.-based financial services organization initiated a migration from legacy Sybase ASE and Oracle databases to PostgreSQL on AWS. The environment included a large volume of SQL code and embedded business logic supporting critical financial operations.

The objective was to consolidate infrastructure, reduce proprietary licensing costs, and enable scalable cloud deployment while maintaining strict compliance requirements.

Following a detailed assessment phase, automated conversion tools were used to migrate schema objects, data, and procedural logic. The organization is transitioning toward a unified PostgreSQL architecture that supports improved scalability and long-term cost optimization without compromising operational continuity.

From Delphi to C# application modernization

A U.S. manufacturer operating a long-standing Delphi-based application required modernization of its application layer while retaining its SQL Server database.

The project involved tens of thousands of lines of code. A hybrid approach combined automated conversion with targeted manual refinement for specific interface components. During testing, performance optimizations were introduced to ensure compatibility with modern connectivity libraries.

The resulting C# application provides improved maintainability and integration flexibility, supporting the company’s ongoing operational requirements.

Final thoughts

Outdated software introduces cumulative risks that affect security, performance, compliance, and resource allocation. These risks rarely manifest as immediate failures, but they influence long-term business performance and strategic flexibility.

Modern platforms, by contrast, are designed around continuous updates, scalability, and integrated security practices. Structured modernization, supported by automation tools where appropriate, allows organizations to manage transition risk while positioning their technology infrastructure for sustainable growth.